Productivity and Human Body: Centuries of evolution in the automotive industry

The industrial history of the automobile illustrates a persistent paradox: every gain in productivity has come with new physical constraints for workers. From mechanics to automation, each innovation has pushed the boundaries of productivity.

But at what cost to workers’ bodies? Tracing the evolution of the automobile through the lens of operators’ health shows that productivity gains and employee well-being have often been in tension—and that this dilemma remains relevant today.

18th – 19th Century: Birth of Industry and the Dawn of the Automobile

The rise of the Industrial Revolution marked the transition from craftsmanship to mechanization and the standardization of tasks. The introduction of steam engines, followed by the first combustion engines, radically transformed the organization of production.

Key milestones:

-

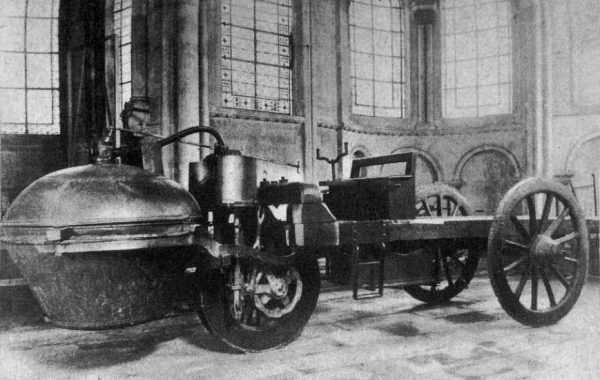

1769: Cugnot builds the first self-propelled vehicle, the steam-powered fardier.

-

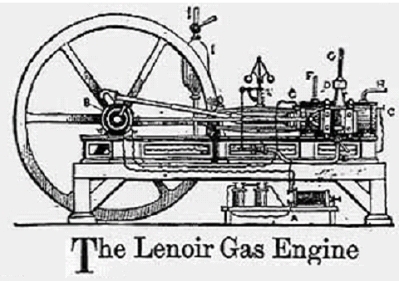

1860: Étienne Lenoir invents the internal combustion engine.

-

1880s: Daimler & Benz refine the engine, laying the foundations of the modern automobile.

Cugnot fardier à vapeur. Source : Wikipédia

Lenoir combustion engine. Source : Wikipédia

Replica of the Benz Patent Motorwagen. Source : Wikipédia

These innovations undoubtedly multiplied productivity, but they also introduced, for the first time, repetitive tasks, exposure to heat and fumes—leading to physical strain for workers as early as this period.

Frequent accidents occurred with belts, wheels, and gears… Engels observed that workers resembled “an army returning from campaign,” so widespread were mutilations.(Source : ANIENIT)

Early 20th Century

Scientific Management (Taylorism) emerged to rationalize work and maximize productivity.

Taylorism (1911) introduced horizontal and vertical division of tasks, time studies, and standardized movements. Ford’s assembly line (Model T, 1908–1913) generalized mass production and parts standardization.

While productivity soared, work became repetitive, monotonous, and physically demanding. This led to fatigue, chronic pain, and the first musculoskeletal disorders (MSDs). These disorders became an early warning sign of the human cost of industrial performance.

By the 1960s, rejection of this model manifested in high turnover, increasing absenteeism, and social conflicts, culminating in the peak of May 1968 in France. (Source : DCG Média)

Ford Model T automobile assembly line, 1913.

Source : Wikipédia

1950s–1970s: Lean, Kaizen, and Pressure on Operators

After World War II, Toyota developed the Toyota Production System (TPS), known in the West as Lean Manufacturing. The system combined just-in-time production, autonomous teams, continuous improvement (kaizen), and waste reduction.

These innovations reduced certain inefficiencies and increased flexibility, but they also intensified work pace and multiplied musculoskeletal disorders (MSDs) affecting shoulders, wrists, and backs—first in Japanese factories, then globally.

Even with improved ergonomics and the presence of occupational physicians, accidents and work-related illnesses remained frequent.

Japanese journalist Satoshi Kamata, who infiltrated Toyota’s Nagoya factories for several months in the early 1970s, reported that official figures were scarcely disclosed, yet cases of accidents, occupational diseases, suicides, and Karōshi (sudden death from overwork) were very real.

1980s–2000s: Robotization and Globalization

Automation and robotization became widespread to improve safety, quality, and standardization. Operators increasingly took on supervisory roles, responsible for monitoring or feeding machines. Globalization further intensified pressure on work pace and productivity.

However, musculoskeletal disorders (MSDs) became the leading cause of occupational diseases in France by the 1990s. It was also during this period that a turning point emerged: the 1991 reform of Table 57 of occupational diseases expanded recognition of pathologies related to repetitive movements and periarticular injuries.

Awareness of MSDs in the automotive industry spread rapidly. Many ergonomists working within major industrial groups focused their research and interventions on the prevention of these disorders. (Source: SELF)

Today: Industry 4.0 and the Persistence of MSDs

Since 2011, Industry 4.0 has been transforming the automotive sector with 3D printing, augmented/virtual reality, IoT, cloud computing, big data, and artificial intelligence.

Over three centuries, working conditions for operators have significantly improved, thanks to new regulations, safer environments, and better quality of work life.

Nevertheless, musculoskeletal disorders (MSDs) persist. Traditional risk factors in the automotive industry remain, alongside new physical, organizational, and psychosocial constraints.

Today in France, MSDs account for approximately 87% of recognized occupational diseases, resulting in 22 million lost workdays each year across all sectors. (Source: Ameli)

Conclusion

The industrial history of the automobile shows us that every technological advance has always come at a cost to the human body.

From the 18th-century steam engines to today’s smart factories, working conditions have improved, yet musculoskeletal disorders (MSDs) remain a current challenge.

This ongoing tension between performance and health calls for a rethinking of work organization, ergonomics, and prevention, while exploring how Industry 4.0 could reconcile innovation, efficiency, and operators’ well-being.

Sources :

Ameli – Les TMS : définition et impact https://www.ameli.fr/entreprise/sante-travail/risques/troubles-musculosquelettiques-tms/tms-definition-impact

Anienit – La naissance du monde ouvrier en Europe (1815-1880) https://www.anienit.org/new-s-bil/article/la-naissance-du-monde-ouvrier-en-europe-1815-1880/102#:~:text=Le%20monde%20ouvrier%20est%20un,un%20travail%20d%C3%A9coup%C3%A9%20et%20r%C3%A9p%C3%A9titif.

DCG Média – La crise du fordisme des années 1960 https://www.droit-compta-gestion.fr/economie/histoire-des-faits-economiques/prosperite-crise-et-mondialisation/crise-et-mutations/la-crise-du-fordisme-annees-1960/

DCG Média – OST de Taylor et TMS : Analyse des risques pour les ouvriers https://www.droit-compta-gestion.fr/management/la-theorie-des-organisations/les-premices-de-lanalyse-des-organisations/ost-de-taylor-et-tms-analyse-des-risques-pour-les-ouvriers/

Encyclopédie d’histoire numérique de l’Europe – Organisation scientifique du travail : concepts, techniques, contestations https://ehne.fr/fr/encyclopedie/th%C3%A9matiques/civilisation-materielle/l%27europe-au-travail/organisation-scientifique-du-travail-concepts-techniques-contestations

Paul Jobin – La mort par sutravail et le toyotisme https://www.researchgate.net/publication/292774417_La_mort_par_surtravail_et_le_toyotisme

Melchior – Le toyotisme comme nouvelle forme d’organisation du travail https://www.melchior.fr/exercice/document-4-le-toyotisme-comme-nouvelle-forme-d-organisation-du-travail

SELF – Repère thématique 1 : Les troubles musculosquelettiques https://ergonomie-self.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/rt-tms.pdf